by Hecson Olguin

Approaches to naming EVs have led to messy brand architecture decisions. Why does BMW EV product naming stick to tradition while Tesla goes with chaos? With the EV’s increasing in popularity, especially models from new companies, naming EVs is a point where everyone is approaching brand architecture in a different way.

Will structure prevail, or will innovation and flexibility redefine how we go about naming EVs?

The EV market is rapidly expanding, with companies both old and new vying for attention and market share. However, one of the less discussed aspects of this growing industry is the importance of brand architecture, particularly how EVs are named.

The automotive industry typically approaches naming EVs in two distinct ways: a numerical systematic approach, exemplified by brands like BMW, and a more traditional naming strategy, often lacking a clear system, as seen with brands like Toyota and Chevy.

The first approach utilizes alphanumeric designations to convey information about the vehicle, while the latter employs names that resonate culturally or emotionally, prioritizing memorability over systematic structure.

A clear, structured EV naming system helps brands create a distinct identity and recognition among consumers. A lack of consistency might confuse or alienate potential buyers. But at the same time, the most powerful EV names are evocative and signal the product’s positioning and purpose in a more emotional way.

BMW’s not so interesting yet functional approach to brand architecture

BMW is famous for its precise and structured approach to car naming, aligning seamlessly with its brand positioning as a manufacturer of finely engineered vehicles—“ultimate driving machines”

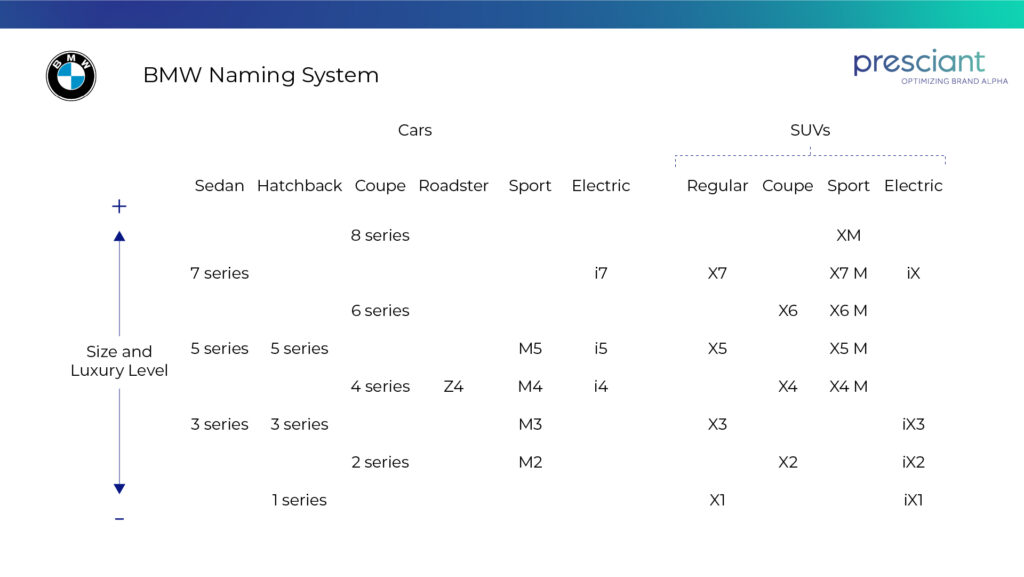

Across its traditional lineup, the brand employs a systematic car naming convention that reflects vehicle series, engine type, and occasionally even the powertrain technology, ensuring clarity and consistency across its offerings.

BMW’s car naming system uses series numbers (like 3 Series) combined with a suffix to indicate engine size or technology, with higher numbers typically signaling more power or advanced features. Odd numbers are for sedans, even numbers for sportier coupes, and the X Series designates SUVs.

This meticulous nomenclature extends to its electric vehicle lineup as well. The “i” series signifies BMW’s electric models, with many retaining the core characteristics of their gasoline counterparts, such as the Series 5 and its electric variant, the i5. This structured approach to naming EVs facilitates clear product identification and enables BMW to seamlessly integrate EVs into its lineup while maintaining its traditional brand framework.

Tesla’s unstructured approach to naming EVs is creating a mess

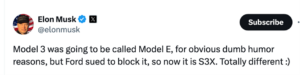

Tesla’s approach to electric vehicle naming stands in stark contrast to BMW’s structured system. While BMW employs a meticulously organized car naming architecture, Tesla embraces a more relaxed and straightforward method. The names of Tesla’s vehicles—from the Model S to the Model Y—are memorable in their simplicity and appear to be a deliberate emulation of BMW’s famous approach. However, it doesn’t exactly work and doesn’t end up as a cohesive brand architecture.

It seems like Telsa started out on the BMW track and then Elon Musk got bored with it. One of the most inventive aspects of Tesla’s naming convention is how the lineup—Model S, 3, X, and Y—deliberately spells out “S3XY”, supposed to reference “sexy”. This playful arrangement reflects Tesla’s disruptive spirit, adding a lighthearted touch that differentiates the brand. Does it work though? I don’t think so. Especially since Ford sued to make Tesla drop the “E.”

The Model S, signifying “sedan,” was followed by the Model X for “crossover,” The Model 3 was originally intended as Model E and the last one in this frivolous l spirit was Model Y. However, after “S3XY,”even if it worked, the question arises: how many more letters can the brand realistically incorporate?

As Tesla expands its lineup, it seems to have abandoned the attempt at a structured EV naming convention. The latest releases are the Cybertruck, along with the anticipated Tesla Semi—and the eagerly awaited Tesla Roadster. The Cybercab and the Robovan are the newest launches. These approaches to naming EVs totally deviating from the original naming pattern.

These models do not adhere to the “Model” prefix and fall outside the “S3XY” acronym, raising questions about how Tesla will maintain brand clarity and coherence as it ventures into new territory.

BYD is taking the Toyota way

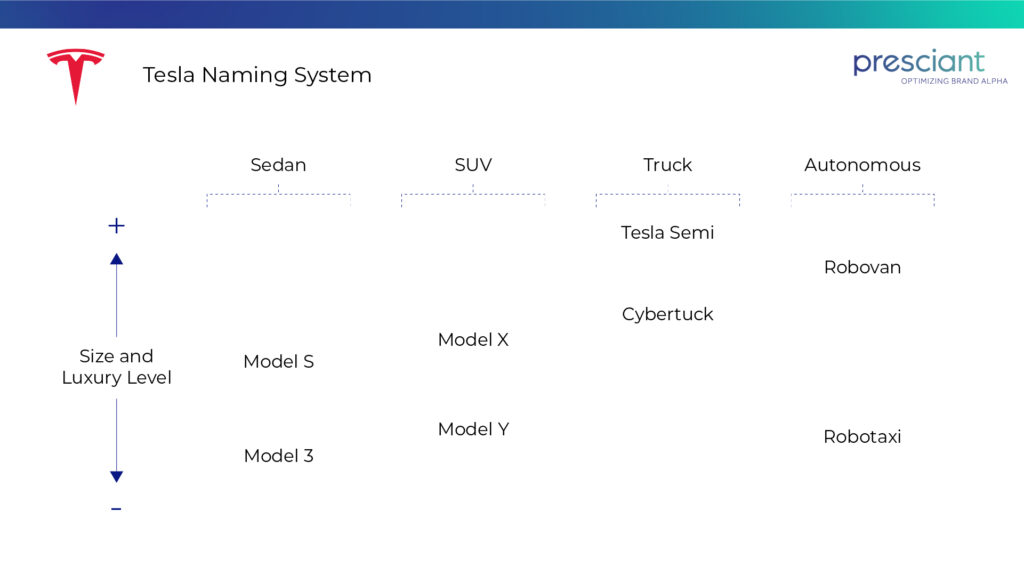

BYD’s naming structure avoids the use of numbers. It takes an EV naming approach that is similar to the traditional auto makers, including GM, Ford and Stellantis i.e. choosing completely different brand names for different models. Specifically, BYD aligns with the strategy for naming EVs used by brands like Toyota and Hyundai: Different brand names for models targeted at different audiences. The brand features two primary series: “Dynasty” and “Ocean.” This strategy effectively distinguishes its luxury offerings from more mainstream models, with the Dynasty series targeting higher-end buyers and the Ocean series catering to budget-conscious, eco-friendly consumers.

Prioritizing simplicity and clarity, BYD favors EV names that are easy to remember and pronounce, though not all of their car names carry through with names relevant to the sea. While the “Ocean” series includes names like Dolphin and Seal—animals commonly associated with the ocean—it also features EV names like King and Song, which have no direct connection to water.

The “Dynasty” series is named after historic Chinese dynasties, such as Han, Tang, and Qin, evoking a sense of tradition and luxury.

It is a complex EV naming system likely to pose challenges in global markets, where the cultural significance of these brands is unlikely to effectively translate. References to Chinese dynasties may work well in China, but these names will lack resonance in international markets, where emphasizing China will heighten the concerns about quality already associated with Chinese cars.

As BYD expands internationally, the China-centric EV naming issue is already becoming clear. BYD has been forced to introduced localized naming systems. For example, one model already has three different names, depending on the region: Destroyer 05 in China, Chazor in Uzbekistan, and King in Brazil and Mexico.

There is also a noticeable inconsistency in the name classification and visual design systems in use within each of the two series. The brands don’t fit the positionings. For instance, a vehicle that embodies the characteristics of the Dynasty series might be labeled under the Ocean series, while some models in the Dynasty lineup may not exhibit the expected luxury performance.

No matter what you do, stick to it and be consistent

These companies exemplify three different approaches to naming EVs: A systematic numerical coding method, a branded naming strategy, and Tesla’s weird blend of both. None is ideal.

We could explore various EV naming strategies for hours, such as Chevrolet’s perfunctory simplistic tactic of adding “EV” to existing model names. For example, “Equinox EV,” a car which has nothing in common with the gasoline version.

In contrast, BMW makes only slight modifications to the models within the same family name, as seen with the Series 3 and i3, preserving brand consistency. BMW excels at expanding its electric lineup while respecting existing model names. For instance, with the “iX,” there is no room for confusion since there is no “Series X” to complicate matters.

BYD is trying for a more emotional, evocative naming strategy, but it suffers from poor implementation. There are so many inconsistencies on a global scale. For example, in Colombia, there is a “Song Plus,” while the same vehicle in Mexico is called “Song Pro.” Additionally, Mexico has its own “Song Plus,” which is entirely different from the Colombian version, creating confusion despite the shared name. What a mess!

While both ultra disciplined and evocative strategies for naming EVs have their merits, the key is to choose one and execute it effectively. It’s an ongoing effort that companies must prioritize to prevent future complications. Neglecting to think carefully about naming EVs and developing a thoughtful brand architecture can lead to an unmanageable situation in a few years, with significant financial consequences that no one will want to face.