By Yitzchak Grant with Joanna Seddon

The brand disaster of the Kraft Heinz merger

The brand disaster of the Kraft and Heinz merger began with the deal engineered by Warren Buffet and 3G Capital. They touted the promise of the merger: scale, efficiency and value growth. Warren Buffet invested $10 billion into the new entity and said: “This is my kind of transaction, uniting two world-class organizations and delivering shareholder value. I’m excited by the opportunities for what this new combined organization will achieve.” The merger was welcomed by analysts and media as heralding efficiencies, brand power, and stable cash flows.

It didn’t work. Before the merger the market cap of Kraft was $40 billion and Heinz, which was private, was bought for $28 billion—a total of almost $70 billion. The market cap now is less than half—$32 billion. Kraft Heinz has written off over $37 billion in goodwill and intangibles, almost twice its current market cap.

Loss of brand value is the major part of the Kraft Heinz disaster: More brand value has been destroyed than remains, since brand constitutes the majority of intangibles for consumer products companies.

Now, they are splitting up the companies again, acknowledging failure.

What went wrong?

The excuses: shifting consumer tastes and preferences away from older products such as Kraft Mac & Cheese and Heinz.

As Jim Meier of the Marketing Accountability Standards Board says: “The real reason is quite different.” Both companies entered the merger underinvesting in their brands. At the time of the deals, Heinz was spending just 2.2% of sales on advertising, Kraft 2.5%. This compares to similar companies such as Hostess, and Constellation, owner of brands such as Corona, Modelo, and Mondavi, which were investing 2-3x that, while Boston Beer was spending over 20% of sales on advertising.

When the merger came, the new Kraft Heinz company doubled down on weakness. Instead of scaling brand investment, it scaled cost cutting. The new owners behaved like typical private equity owners—they cut people, they cut budgets. They eliminated 17,000 jobs and imposed Zero-Based-Budgeting (ZBB). As Jim puts it, “Zero Based Budgeting eviscerates a marketing budget.” Marketing spend hovered below 4% of sales, roughly half that of peers. On paper, ZBB looked like financial discipline. In practice, it turned every marketing dollar into a yearly fight for survival.

A brand disaster told by the numbers

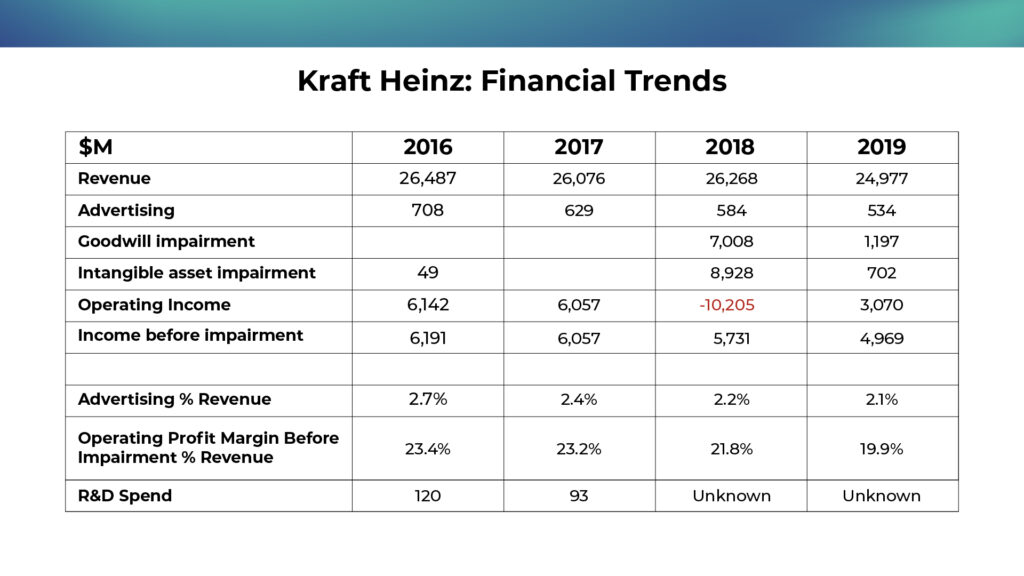

See how the brand disaster played out over the first few years:

Each year less and less was spent on advertising even relative to revenue, and R&D spend declined to a point where it was no longer reported. The result, declining or flat sales and declining profit margins.

It is not surprising that brand value plunged.

What Kraft Heinz did not understand about creating and sustaining brand value

To survive, brands must remain relevant in the minds of consumers. They require constant investment to be considered by people at the point of purchase and consumption. This requires vigilant brand managers who have a relentless focus on their consumers, creating moments of emotional connection to achieve saliency across occasions. We know consumer trends are shifting, but while this means former consumption occasions are declining, new ones are growing with new needs and new innovation opportunities.

Innovation is the life blood of brands. Each year, a brand needs something new to maintain interest and stimulate growth. Steve Jobs knew this—an iPhone innovation every year, even though it might be quite a small one, e.g., iPhones in myriad colors.

Kraft Heinz spent less and less on marketing and innovation

Kraft Heinz had over 100 brands in its portfolio, but there weren’t enough marketing dollars to go around! Poor Jell-O had to wait 10 years for a marketing refresh in 2023—something that should have happened every year! Brands such as Kraft BBQ and Salad Dressing, Bagel Bites, Cool Whip, Kool Aid, Crystal Lite and others haven’t got any advertising at all since the merger.

Innovation has been just as poorly served.

Yes, Kraft Heinz occasionally produced novelties — a ketchup smoothie with Smoothie King, Lunchables PB&J, or flavor extensions in condiments. But these were gimmicks, not platforms for growth. They filled headlines, not households. Maxwell House had just one innovation—ice latte with foam. The press release on the Kraft Heinz website states that this is part of “the first rebrand in nearly ten years!” Hardly something to be proud of.

Meanwhile, the big strategic push was framed around sustainability. Laudable in theory, but in practice it was cost-cutting: Kraft Real Mayo in recycled PET jars, Shake ’n Bake without the plastic shaker bag, thinner shrink-wrap and reduced plastic SKUs. What they actually did was reduce package sizes—22 instead of 24 slices in a Kraft American Cheese package, smaller Mac & Cheese boxes, salad dressing bottles and Philadelphia Cream Cheese tubs, more sauce and fewer beans in a can of Heinz baked beans. This is “shrinkflation”—cost cutting in disguise.

Other companies have invested in brand and innovation to build value

The scale of the brand disaster becomes clear when you look at how other companies make brand and innovation investments that paid off.

When Hostess came out of bankruptcy in 2016, it reinvested 8–10% of sales into marketing and restarted innovation. The result was that the business more than recovered; it created tremendous brand equity. It was sold to J.M. Smucker for $5.6 billion in 2023 — nearly triple its earlier value.

Constellation Brands spends about 9% of sales on marketing. The result—Corona and Modelo brands are among the fastest-growing beers in the US.

Boston Beer has resurrected its fortunes and is growing as a result of spending 20%+ of sales on marketing, fueling sustained relevance through Sam Adams, Truly, and Twisted Tea.

These companies treated marketing and innovation as growth capital, not discretionary costs. Kraft Heinz went the other way.

Kraft and Heinz splitting again—double jeopardy

What does the split achieve?

Not much, beyond financial housekeeping. Each successor company inherits not only household names, but the consequences of neglect: eroded brand equity, faded consumer relevance, a decade without innovation spend, and a marketing culture that has been trained to defend, not build.

Splitting the balance sheet doesn’t split consumer perception. And it does not reverse the brand disaster. The ketchup doesn’t suddenly taste fresher because Wall Street sees two tickers instead of one.

The bigger lesson

Kraft Heinz’s split is cast as a reset. Two leaner sharper companies free from the consequences of the mega-merger. But it isn’t a rebirth story. It’s the logical endgame of a decade spent liquidating brand equity and failing to innovate. Dividends and buybacks may have kept investors warm for a while, but at the cost of the very thing that created cash flows in the first place.

Takeaways

The takeaways for anyone watching aren’t about ketchup or cheese. They are about the currency of brand.

- Cut marketing, and you accelerate decay.

- Get rid of people, and you cut the capacity to innovate.

- Stop innovation, and your brands become old.

- Reduce package sizes, and you undermine trust.

- Treat brand as expendable, and eventually you run out of brand to spend.

Final thoughts on the Kraft Heinz brand disaster

Kraft Heinz is being split in two, but it was hollowed out long before. The numbers don’t lie: more value has been destroyed than remains. A true brand disaster.

The real question isn’t whether the split creates two stronger companies. It’s whether there’s any brand equity left to split at all.