Joanna Seddon, Managing Partner

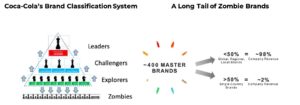

Coca-Cola has publicly announced that it is trimming down its portfolio and getting rid of half its portfolio – 200 brands, which the company, with its usual flair for naming, has decided are “zombies”. Coke has developed a classification system based on market position and maturity which goes from Leaders, billion dollar #1 brands such as Coke and Sprite, to Challengers such as Minute Maid and Simply to high potential Explorers, such as AHA and, at the bottom, the poor Zombies, which are to be axed.

Coca-Cola is not the first to spectacularly rationalize its brands. Some years ago, Unilever stripped down from 1600 to around 500. It won’t be the last. Companies tend to go through cycles of brand expansion and proliferation and then burst. The Unilever number has crept up again to around 1,000.

Why does this happen? And does it make sense? Our view is that it shouldn’t, and it doesn’t.

We believe that it reflects a systematic lack of understanding of the importance of brand portfolio architecture across many major corporations. This leads them to miss out on huge opportunities to achieve higher sales and profit growth.

The causes of this are clear.

Responsibilities are allocated and budgets set brand by brand. That’s where the P&L’s sit. Each brand within a portfolio operates in a vacuum, pursuing its own objectives, rather than thinking of the good of the whole. Other brands from the same company are viewed as competitors, encouraging them all to crowd together in the same space.

There is devolution of decision-making about brands to individual product groups or markets. Each believes that they have the freedom to invent, name and position new brands at will. The worst are the tech companies. The engineers say, “Look at this great new product (or variation or evolution) I’ve come up with, let’s order pizza and name it over lunch”. But consumer focused companies aren’t much better. Each group sees its target consumers as different, and local market conditions as special and believe this empowers them to adopt a different brand approach.

Businesses are plagued by short-termism. This is how objectives are set and brand managers rewarded. Marketing and innovation budgets are allocated to whatever is most likely to achieve the next quarter’s, or the next year’s sales goals. This encourages experimentation with many things and the pursuit of whatever is latest and greatest, no matter how short lived.

Managers think “small picture”. The pressure to deliver right now forces focus on whatever will make an immediate difference, no matter how small or incomplete. There’s no tolerance for initiatives which will take time to take effect, even if the potential impact is immense.

There are real truths behind all this. It is wonderful and desirable to have brands run by people who truly live and breathe them. It is critical for brand and marketing strategy to adapt to local cultures and needs. It is always necessary to create excitement and buzz in the moment and drive sales short term. But it is not enough.

It is these attitudes and behaviors which lead portfolios to blow up, through an uncontrolled proliferation of brands, sub-brands, variants, extensions, flavors, formats, and technology iterations. Marketing spend is fragmented across too many brands, losing its effectiveness. Investment in innovation splits across too many initiatives, with not enough being spent to allow any to become breakthrough. The company loses its relevance and competitive edge, under attack both from major competitors and disruptors, and is forced back into a defensive position. It is when this is recognized that the drastic portfolio pruning reaction occurs.

Will zombie-killing benefit Coca-Cola? Undoubtedly, in the short-term. If these 200 brands really only account for 2% of sales, eliminating them will allow the company to focus on big brands, such as Coke and Sprite, to reinvigorate Minute-Maid, develop Costa Coffee and invest behind cooler “Explorer” brands such as the sparkling mineral water Topo Chico. But the list also includes well-known names such as Odwalla and Tab. Some healthier, more future-oriented brands may also be at risk: Coke Life, which includes natural zero calorie sweetener stevia (aka Truvia), and potentially Dasani. Others being sacrificed have strong local constituencies: fans of the almost 100-year-old cult classic Northern Neck Ginger Ale, a regional Virginia brand are already on the warpath, determined to save it.

There are two sides to the coin. Uncontrolled brand proliferation can drag the business down. Brand rationalization brings its own dangers. It involves immediate short-term sacrifice of revenues and profits, as products are killed off and businesses sold. And it is easy to overdo. Withdrawal from parts of the market creates space for competitors to enter and make inroads into the core businesses. Future opportunities may be missed and snatched by others —PepsiCo for example, has launched Driftwell, which helps you sleep. Consolidation of small brands and elimination of sub-brands can cause potential customers to overlook products which the brand is less known for. This happened recently to Ogilvy, when Ogilvy PR and many other sub-brands were consolidated into one Ogilvy. The larger, older-established advertising brand drowned out the others. New brands and sub-brands can play an important part in signaling innovation and change in strategy. Google changed the name of the company to Alphabet to stop the search brand drowning out its smaller, sexier, future-oriented initiatives such as Calico, Verily and Nest. It worked and the share price soared.

The cycle of brand boom and bust can be avoided. The prescription is simple (though not easy to implement). It has five parts:

- Start from the future and work back to the present. Identify the biggest future market opportunities.

- Make customer needs within the category the starting point. Determine what products are needed to meet the biggest consumer needs.

- Look at your brands through a portfolio lens. See which brands fit best with the future market opportunities. Identify gaps where you don’t have brands.

- Balance your marketing budget allocation and innovation investment between building the brands you need for the longer term and supporting the business in the present.

- Prioritize, prioritize, prioritize. You may not need to kill non-priority brands. You can let them fade away.

Joanna Seddon is Managing Partner of Presciant, a new brand consultancy dedicated to optimizing ‘brand alpha’: helping companies use brand to gain a financial edge. Before this, she was President, Global Brand Consulting at Ogilvy for 10 years. Prior accomplishments include creation of the BrandZ Top 100 global brand valuation ranking for WPP/Kantar. She is a board member and Past President of the AMA New York, Chairs the Marketing Hall of Fame and is the recipient of the 2020 MASB Marketing Accountability Award.