by Yitzchak Grant

Brand failures in M&A are common. Indeed, M&A is a brand trap – most companies walk right into it.

In every M&A deal, there’s one line item that gets overlooked—and it’s usually the most valuable.

Not operations. Not finances. Not org charts. Not culture.

The brand.

For all the spreadsheets, financial modeling, and due diligence, brand is often treated like an afterthought. And it shows.

KPMG found that 83% of mergers fail to boost shareholder returns

One major reason for strategic failures: Companies merge, brands don’t.

It doesn’t show up on the balance sheet, but it shows up in customer confusion, eroded equity, and lost revenue–true brand failures.

Let’s look at the scoreboard.

Case Study 1: Kraft Heinz Merger– Cost synergies, brand erosion

When Kraft and Heinz merged in 2015, the playbook was classic 3G Capital: slash costs, optimize ops, scale efficiencies.

It worked—on paper.

But the brands suffered. You can add this case to the list of M&A brand failures.

Between 2017 and 2019, Kraft Heinz wrote down the value of Kraft and Oscar Mayer by over $15 billion. In 2021, they took another $2.9 billion impairment.

Why? Because brand equity had been drained through underinvestment and poor architecture. Advertising budgets were gutted. Innovation slowed. Brand relevance collapsed.

The company chased synergies and lost sight of strategy.

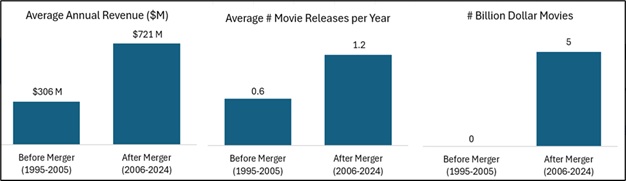

Case Study 2: Disney + Pixar Merger– Brand as a strategic asset

Now contrast that with Disney’s acquisition of Pixar.

Disney didn’t just preserve Pixar’s brand—they protected it. Steve Jobs remained on the board. Pixar kept its culture, leadership, and storytelling process. The result?

Hits like Up, Inside Out, and Coco. And a revitalized Disney animation studio that learned from the best.

Brand wasn’t just integrated—it was leveraged. The equity of both brands grew stronger. No brand failures here.

Here’s the M&A blind spot:

Most companies think brand is just a logo, a name, or a campaign.

It’s not.

Brand is how value is signaled. It’s how trust is built. It’s how pricing power, customer loyalty, and market differentiation show up in real terms.

And in M&A branding decisions, if you don’t understand:

- Which brand holds the most equity

- What your customers actually associate with each name

- How your architecture is going to evolve

…you are likely paying for assets you’ll quietly destroy post-acquisition, leading to costly brand failures.

The five brand traps of M&A

1. False equity assumptions

Just because a brand is known doesn’t mean it’s strong. We’ve seen household names that test worse than private label when you strip away nostalgia.

2. Identity confusion

Merging two brands into one hybrid Frankenstein dilutes meaning. “Yahoo-AOL”? “Sprint-Nextel”? Those weren’t combinations. They were compromises.

3. Cultural incompatibility

Brand is culture, expressed outward. If two companies don’t align on values and voice, no amount of synergy will save the story.

4. Emotional decision making

Brands are emotional – but brand decisions shouldn’t be. If your naming choice isn’t grounded in strategy, its grounded in ego.

5. Leaving it to the lawyers

Brand matters. When the accountants and lawyers make the branding decision, it’s probably wrong. Marketing must have a voice – to protect and grow value.

What winning companies do differently

- They audit brand equity before signing the deal.

- They run brand valuation in parallel with financial valuation.

- They map brand architecture for the long-term—not just launch day.

- They use brand as a strategic lever, not a design project.

At Presciant, we help businesses avoid brand failures in M&A by putting the brand strategy front and center—before the ink is dry.

Because here’s the truth:

If brand isn’t part of the deal model, the model is broken.

Final thoughts to avoid brand failures in M&A

Future customers don’t care about your synergy targets. They care about clarity, meaning, and relevance.

If brand value isn’t carried forward — whether through preservation or transformation — growth stalls before it starts.

So next time you’re in the boardroom signing off on a deal, ask this:

Do we even know what we’re buying?

Because if no one’s valuing the brand, you’re about to overpay and suffer the losses of brand failures.